This is the third article in my series that came out of a discussion with Lawrence M. Schoen of the Klingon Language Institute. Previously (in Part 1 and Part 2), Lawrence educated me about how the KLI started and then on the Klingon language itself. Now, we started talking about the Klingon language in Star Trek: Discovery, which somehow turned into a bit about Shakespeare!

Adeena: Right now, with all the new Star Trek series… We’ve got Discovery, we’ve got Lower Decks, we have Prodigy. Is there an influx of people who are interested in Klingon, especially with Discovery’s first season having a very Klingon flair to it?

Lawrence: Well, in fact, there are a couple of people in the Klingon Language Institute who were hired by CBS to work on Discovery.

Adeena: Oh, nice!

Lawrence: All the Klingon in that first season of Discovery is accurate Klingon, which can’t be said of any Klingon you hear in earlier spin offs. They’d work out the language and then pass it on to the voice coach, who then had to train the actors. A couple of actors have really gotten into the language, and that’s a lovely thing. A KLI member in Germany was hired to provide Klingon subtitles for all the episodes for European broadcast. So that was kind of fun as well.

But all this was happening at the same time Duolingo came out with their Klingon module. It’s probably not a surprise to learn that KLI members worked on that and made that happen.

Adeena: So Duolingo is responsible for the most recent spread of the language?

Lawrence: To a large extent, yes. Duolingo hit, and suddenly anybody who had a passing interest in Klingon could take it up. And Discovery came out at about the same time. Suddenly, there was an explosion of interest, both as measured by all the people signing up for the language in Duolingo, and an influx of new members joining the KLI. Right now, we’re seeing a renaissance, if you will, of Klingon speakers that harkens back to the very early days of the KLI. A handful — let’s call them “Young Turks” — armed with a language for doing things that have never happened before, like translating Hamlet, or Gilgamesh. Now we have even more of these people, as evidenced by recent efforts. In 2021 we released a translation of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Another person did a massive, full length original novel in Klingon that was also published this past year, and on and on like this. It’s a beautiful thing. Also, there’s more discussion overall and more people engaged in this discussion. And the participants are from all over the world. Because as Discovery has gone out into the world, particularly that first season and made people hear Klingon, and as Duolingo has extended its reach, we’ve had more people coming in. That’s wonderful.

Adeena: Speaking of writing in Klingon… You’re a science fiction author, too. Have you ever written any fan fiction set in the Star Trek universe with Klingons? Even just for yourself, just for fun?

Lawrence: I’ve done better! I wrote the first, possibly the only, short story entirely in Klingon for a Star Trek anthology from Pocket Books. I wrote it in Klingon—I didn’t write in English and translate it. I wrote it in Klingon. When I sent it in to the editor, the editor came back to me said, “I need to know what this says. Because everything has to be run by the lawyers at Paramount.” And I replied, “I don’t have an English translation!” So I had to write a translation of it.

It was a very Klingon story about honor, but also a grammatical quirk in Klingon that prompted the story: Klingon as a language uses suffixes to tell us a lot of things. One of them is a negation suffix. But there’s another suffix, -Ha’, which indicates that whatever the action of the verb may be, it wasn’t done properly. Typically, you might think it translated as the English prefix of ‘mis-‘, like you mishandled something, or ‘dis-‘ you disarm something. But it conveys not the proper way to do this action. And there’s the word in Klingon, jub, which means to be immortal. I wanted to know what jubHa’ meant, because one of the things you can do with suffixes, you can put them on words that you’d never think to pair them with. So what does it mean to be “dis-immortal?” I wrote a story that answered that question.

I took a Klingon warrior who was infected with a Romulan secret weapon that left him completely paralyzed. But he couldn’t be killed. You could shove a knife in his heart and when you took it out, the heart healed, and on and on. This was the uttermost agony for the warrior. He could not die in battle. He couldn’t move. All he could do was suffer. And the rest of the story was solving this problem for him. It was a fun little story and appeared in Strange New Worlds III, which was part of a series of anthologies from Pocket Books that invited fans to write Star Trek.

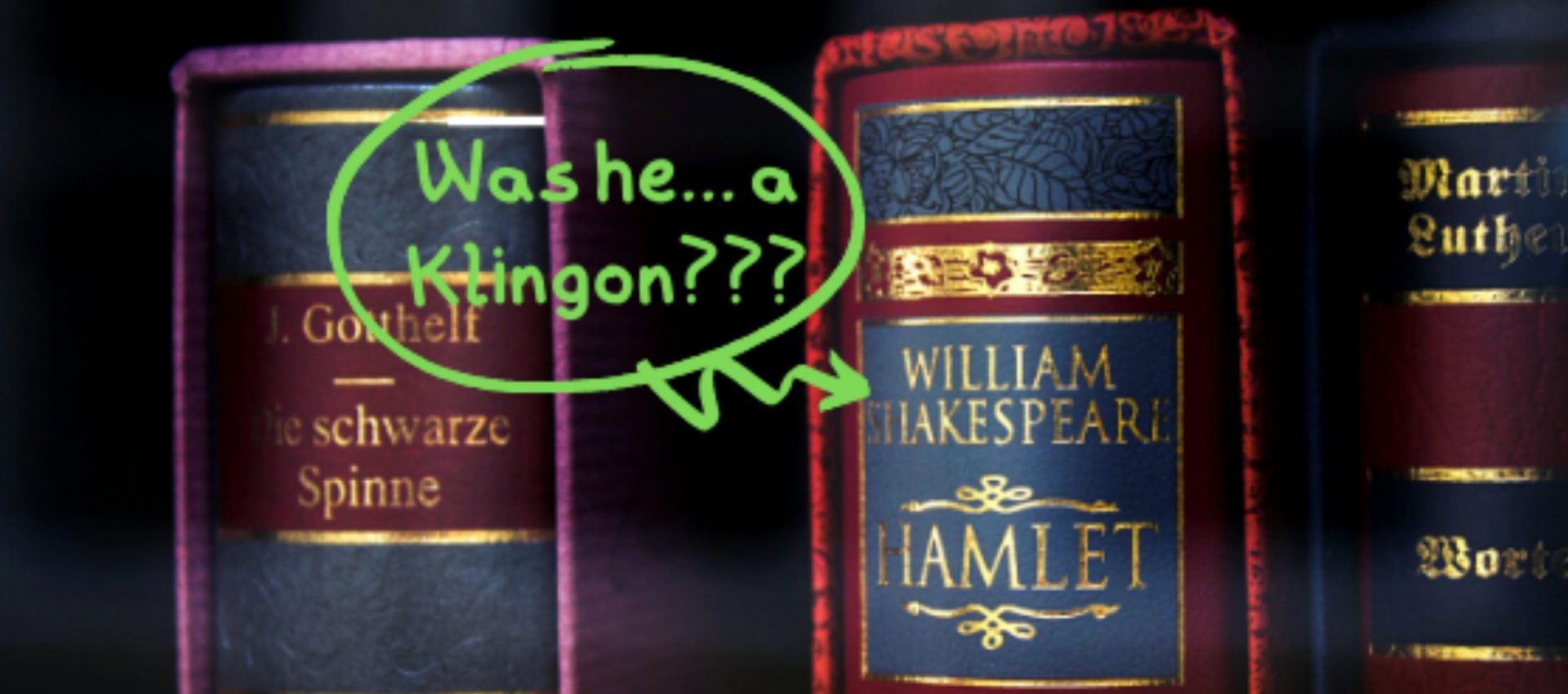

Adeena: I understand that there is Shakespeare in Klingon as well

Lawrence: Indeed! The KLI published a restoration of Hamlet. I wrote an appendix as a professor at Starfleet Academy in which I talked about Shakespeare and asked was he Klingon or not? Because — and this is one of the things that really excited me about the language — we have that line in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country. The Klingons come over for dinner and General Chang says, “’Cry havoc, and let slip the dogs of war!’ You cannot appreciate Shakespeare until you’ve read him in the original Klingon.” And nobody blinked! We didn’t even get an eyebrow raised from Spock. Nobody had an issue with the statement. Which means surely it must be true!

So, if Shakespeare was a Klingon, then we have hundreds of years of literary criticism and theory perpetuating the lie that Shakespeare was human. Dr. Nick Nicholas, who did the translation of Hamlet, has an introduction that talks about Hamlet as a seditious play on the Klingon homeworld. Because from the Klingon point of view, Hamlet’s horrible! He comes home from school, his father has been killed by his uncle, who then seizes the throne. If Hamlet were a good Klingon, he would have acted immediately, killed his uncle, and taken the throne. End of story. Play’s over early in the first half! But instead Hamlet whines and vacillates, though to his credit he eventually comes to the right decision. It’s a coming-of-age story. But in Nick’s introduction, he describes this as a seditious play because many people back on the homeworld thought it would send the wrong message to Klingon youth if they didn’t read through the whole play. Which I thought was wonderful.

Adeena: That’s very interesting to consider that Shakespeare might not have been human! I’ve always been amazed at what he did for the English language — how many words and phrases we use that he originated. That one person originated. Maybe it was because he wasn’t human.

Lawrence: You start going through the plays and you do a quick summary. Romeo and Juliet? Two warring houses. It’s a Klingon play! Macbeth, the man who would be king? It’s a Klingon play! You look at all the death and mayhem and war… and they’re Klingon plays! How could this be otherwise!? And it all starts to make a disturbing amount of sense.

Adeena: I’m going to be thinking about that for the next week or longer…

Lawrence: Good. Good. It should blow your mind a little bit.

It did… and next time, in my last article in this series, I ask Lawrence a few random questions and he makes an excellent argument why anyone with a passing interest in Klingon should join the KLI!